Glimpses of my journey

Glimpses Of My Journey

Source: Sarojini's Personal Archive

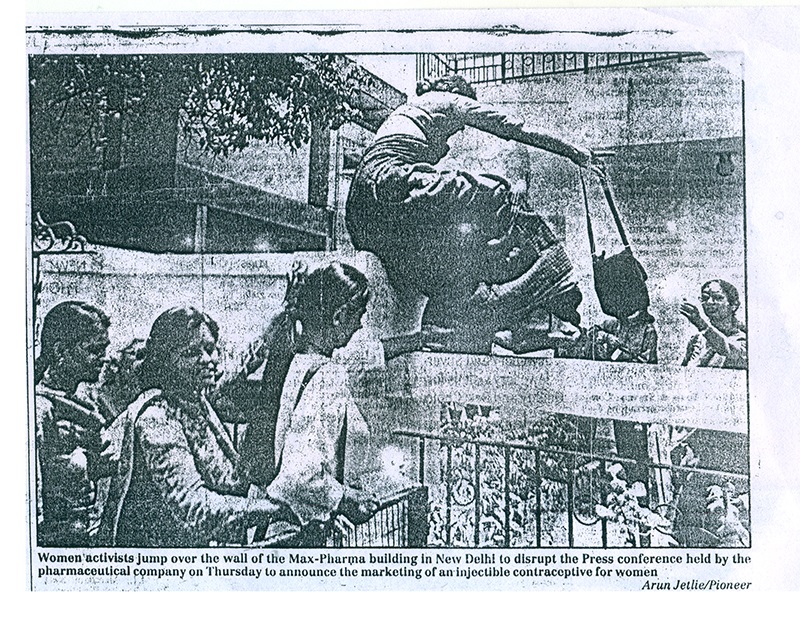

The photograph above (from The Pioneer; 1994) shows a woman scaling a wall. That is me. We tried to enter the Delhi office of a pharmaceutical company when they were holding a closed-door meeting to introduce Depo-Provera, a controversial injectable contraceptive for women. Women’s groups and health groups and networks such as Medico Friend Circle (MFC) were opposing the introduction of long-acting injectable contraceptives for various reasons. These injectables (Depo and Net en) have side effects which are well documented. These include disruption in the menstrual cycle. We knew the big risks it posed for women’s health. Moreover, there is this constant concern about whether our health system is capable of dealing with the safe delivery of a contraceptive which requires intensive medical support and follow up.

When women’s groups such as AIDWA, Jagori, Saheli and people like Brinda Karat came to know about the launch of this injectable contraceptive, we wanted to know on what basis they were launching it in the market. We wanted to know more details related to the trials, risks etc. We sought to participate in that meeting but were refused and physically stopped. Left with no other alternative, we jumped over the wall and forced our way in. While I was jumping the wall along with other colleagues, a journalist clicked a picture. The next day, it was all over the newspapers. Unsurprisingly, front pages carried this photograph of mine with captions such as “unfeminine”. A section of the press accused us of not behaving like “dignified” women. We were labelled anti-choice, anti-development and anti-technology. We were also charged with sensationalism!

When I entered Jagori in Delhi during late eighties (1989 onwards), the campaign against population control policies, anti-fertility vaccines and unethical clinical trials of hormonal contraceptives marked a watershed. And being a part of Jagori, I was actively involved in these campaigns. Personally, the campaign enabled us in Jagori to demystify the deeply hierarchical and technical systems of knowledge in health issues. The ‘nexus’ among doctors, drug companies, international agencies, donors and policy makers has been an important aspect we tried to understand through these campaigns. Intense discussions amongst many of us were sparked off: “How do we talk about choice and rights? Is choice really a choice for women in a patriarchal society? Which is right, what is wrong? What is the difference between population control and birth control?”

The fine line between coercion and choice and the complicit role of many sections of society were challenges that we were facing in campaigns against hormonal contraceptives. We often found ourselves confronting questions of choice, coercion, empowerment and systemic violence in both new and old registers. The medicalisation of poor women’s bodies was disguised in a language of benevolence and empowerment, choice. It disguised private profiteering for big pharma companies and the violation of women’s rights to bodily integrity and health.

Joining the Dots

Jagori was a feminist space which allowed and respected diversity, and yet, at the same time, worked as a collective. There I learnt about feminism and the women’s movement and how the latter addressed issues of patriarchy in its myriad forms and manifestations—violence against women, poverty, population control policies, understanding reproductive rights etc.

What was unique to Jagori was that it worked as a women’s collective. During my journey in Jagori, we worked very closely with other women’s groups such as Sabla Sangh, Action India, AIDWA, Saheli, CWDS and many other organisations networks such as MFC. Jagori was also engaged with organisations working on livelihoods, environment, education and so on in other States, particularly Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Even though I was with Jagori in an urban setting, I had enough opportunities to work with the semi-urban or rural communities in Delhi (with the Sabla Sangh) and in Saharanpur and Banda (Uttar Pradesh).

This period also made me understand collective actions, both institutional and non-institutional. These ranged from organising workshops and trainings with community-based organisations, protests, street plays, wall writings, satyagraha to filing PILs (Public Interest Litigations). Feminist activism, then or now was not perceived as a monolith. Jagori always made an attempt to amplify the voices of marginalised women, and tried to connect their experiences with feminist advocacy on range of issues.

Seamless Interconnections

The culture at Jagori of working with diverse issues and interests is what I learnt and internalised. For any issue related to human rights or social justice, we all used to come together. I remember attending PUDR meetings with Abha to listen to and understand human rights issues. It was just something else! For me it was interesting because I was not just looking at one aspect of empowerment, justice and rights.

Jagori created a space where activists, film makers, researchers, journalists visited and shared their struggles, experiences and sometimes screen films. Even though this was a feminist space, we had film screenings, study circles, meetings and debates on various issues ranging from new economic policies to violence against women. These inputs made us understand the larger determinants which will influence women’s health and empowerment.

I remember once Sanjiv Shah screened his film Famine 87 (or named something like that) at Jagori. Isn’t this interesting? Currently, unless you are working on right to food or another related issue, you don’t get an opportunity to watch such films. We used to get together, screen and watch films on diverse issues. All aspects of women’s lives from employment, wages, increased housework, food availability, access to health care, housing, amongst others were a part of our discussions. Similarly, women’s subjugation in their families and communities and how it has seen increased violence against women and the poor were often a part of our interactions with various activist friends.

We were also involved in the Narmada campaign although briefly. When a huge rally was organised at Harsud against the dam, four of us from Jagori – Madhuri, Weike, Vibha and I, along with Gouri and Sabla Sangh friends from Action India joined the rally in Harsud. More than 60,000 people from all walks of life assembled and joined the march. Even if we worked in a feminist space, we realised that all these issues are interrelated. That was the time Babri Masjid was demolished. We were involved very actively on the issue of communalism. We became a part of Samradayak Virodhi Aandolan and later Peoples Movement for Secularism. We joined hunger strikes at Ferozeshah Kotla and collectively built a piao (a water dispenser) near the protest site as an expression of communal harmony.

At that time, Jantar Mantar was not the only dharna space. You could go anywhere in the city and raise our voices! Most of our protests, marches, sit-ins and demonstrations were held at ITO because it drew a lot of attention. Or India Gate. Our 8 March rallies often started from Darya Ganj. We also organised marches in the Old City too. We would go there a couple of days before the March and paste posters, distribute parchas, even at midnight. We always interacted with local women, had jalebi, kebabs and chai in the old city.

We were not just doing some of the earliest Take Back the Nights in Delhi, but also claiming spaces such as flyovers. We were not scared. At times we were courted arrested. The police would use water cannons to disperse us. Or, they took us in a bus or van,but later dropped us back.

I remember that during one 8th March rally, we wrote all our slogans, messageson peace, secularism and harmony in Urdu, Hindi and other languages. Sheba Chhachhi did the calligraphy, and we had cut and pasted the slogans on sarees. We carried those all over the old city and had a huge rally at Red Fort.

Encouraging Youth and Enabling Spaces for their Participation

I remember once when Veena (Majumdar) di was actively involved with the population control programme. That time Mani Shankar Aiyar was the Minister of Panchayati Raj and we were to send a memorandum to the National Human Rights Commission. Names of people who would go to submit the memorandum were being collected. There was Veena di, Lotika di (from CWDS), Mohan Rao (from JNU) besides others. Veena di said, “Can we have a young person as part of the delegation?” I was the only young person sitting in that crowd, and I became a part of delegation. It was a perfect example of encouraging and involving young people.

Shodhini

Given my interest in health issues, from Jagori was involved in the Shodhini project which had emerged from the women’s movement. I think the idea came during the Calicut Autonomous Women’s Conference and a later workshop that was organised by Fatima Bernard from SRED, Tamil Nadu. Essentially, people who were working on women’s health got together to explore and create alternatives to invasive medicine, injectables and to deconstruct the way we understand biology. It was anchored by Rina Nissim from the Geneva Women’s Health Collective, a nurse who explored herbs and the self-help approach in Costa Rica. Many women’s groups joined in from across the country. Philomena, Renu Khanna, Smita, Bharti Roy, Indira Balachandran, Uma Maheswari, Anu Gupta, Rina Nissim and I were the core team members involved in Shodhini with our respective organisations.

We explored what options could be offered to women. How could we take control of our bodies and create a larger understanding about women’s reproductive health? How do we address the entire issue related to medicalisation?

Thus, Shodhini was born as a collective effort to create an alternative to the prevailing dominant systems for women’s health. Ours was a woman-oriented/centred approach aimed at evolving a simple, natural and cost-effective health care system.It also hada component of reclaiming traditional herbal healing systems, training women to use these for their own health and that of their communities. The Shodhini network facilitated natural and traditional alternatives in health care to meet women’s health needs, particularly reproductive health.

Rina initiated workshops on the concept of self-help, self-diagnosis via breast and abdominal examinations of reproductive organs such as cervix or uterus. So we were imagining the ‘barefoot gynaecologist’. We wondered how we could treat women with plants—not Ayurvedic plants but the ones women used at home! How do we save the knowledge of women healers?

We needed to do a lot of research work for this. I worked on this study along with Bharti in the Doon valley (Shivalik foothills). We spent six months identifying healers. Every month, I spent about 20 days in the Shivalik region and then come to Delhi to document the practices. We would accompany healers to the forests, collect herbs, make herbariums, learn their properties, sit with the team toexamine the properties of that herb (diuretic or astringent), know the toxicity and perform other such exciting tasks. And I also had learnt to identify approximately 100 medicinal plants.

The latter part of this project had more practical sessions which was very challenging, like examinations of breast, bimanual examination of uterus, abdominal examination etc. In the beginning, I was certain I won’t engage. We had to learn all these techniques and to use a speculum. I was very hesitant initially and discussed with Abha. She asked me once, “Don’t you look at your face in the mirror? How different is that from looking at any other part of your body? Don’t you let the doctor to examine you when you go to a clinic for any complaint?” It really made a difference! We are willing to go to a gynaecologist and have her look at our body, but are so uncomfortable to look at our own bodies. I could see the point of it all. It broke the inhibitions that I had with the body and sexuality which were very crucial to well-being.

I was doing bi-manuals, vaginal,abdominal and breast examinations. I could differentiate between various discharges and symptoms, and suggest remedies and referrals. I trained the Sabla Sangh team with Rina and Bharti in working class, resettlement colonies such as NandNagri, Seemapuriand so on. This research was later published by Kali for Women as Touch Me, Touch me Not.

Life and Its Course

During my first pregnancy, the entire Jagori was there to support me and Ranjan. The entire Jagori team—Abha, Maya, Mita, Veena Shivpuri, Kalpana Vishwanath, Juhi, Saroj, Tulsi, Alka, Prem Singh, Weike and Preeti. And others from the extended Jagori family: Sheba, Manjari, Kamla Bhasin and Action India members: Bharti Roy, Gauri, Sharada Behan, Runu, Shanti, the entire Sabla Sangh team. And then, Renuka Mishra, Madhavi and Malini. The list can go on but I might have left out many names.

I remember when my labour pains started Kalpana Vishwanath, Veena Shivpuri, and Malini Ghose were with me inside the labour room. Later when I could not breastfeed my first child, Ritwik, I remember Kamla was so concerned, and so were Abha and Gauri. Since few friends from Sabla Sangh, Reshma, Gyanvati and Maharani had also delivered their babies around the same time, they took turns to feed Ritwik. Even now when some of them meet him, they say “Hamara beta kitna bada ho gaya hai... (Our son is so grown up now). Sharing our joys and issues, our lives were so connected. Once Kalpana was talking about Ritwik’s birth and said, “When we had Ritwik…” It was as if all of us had Ritwik!

Having a child did not restrict my work and activism. Ritwik became a part of our activism and day to day work. Another anecdote. A huge protest against the Bhanwari Devi rape was planned in Jaipur. It was winter and Ritwik was eight months old. All my colleagues from Jagori were travelling in a bus to Jaipur. I did not want to stay back in Delhi. We collectively took a decision that I will go with Ritwik for the protest in Jaipur. During the rally, we all took turns to carry him in a jhola. It was something else: the confidence that we can all do it together.

Around the time of the Babri Masjid demolition, we all thought of spreading our messages related to peace, secularism and communal harmony One midnight, when Ritwik was 11 months old then, we assembled at the Saheli office and carried paints, brushes to paint messages on the flyovers! Midnight ho toh kya farak padta hai? (what difference does midnight make?) We carried him with us and left him in Manjari’s Fiat with her driver. From midnight till three in the morning, we painted messages on the flyovers.

When Ritwik was very young, he noticed that every time someone comes, s/he would be offered water. During our regular meetings there were many emotional moments because we shared very personal stories. Once, when someone was crying, Ritwik came holding a glass of water and said “Pani piyo”.

Jagori Diaries

My journey at Jagori will be incomplete without mentioning Jagori’s diaries. Feminist expression and creativity through poetry, essays and line drawings was as important as anything else to us. Conceptualising and discussing the content was a collective process with many wonderful experiences. The diaries were a part of women’s movement.I really enjoyed working and sketching the diary on Communalism. The entire Jagori team along with friends from Sabla Sangh, Action India, Sheba, Jogi spent nights after nights working together to make the diary happen.

I was fortunate to have had such an invaluable experience of collective learning and doing at Jagori. I never forget to acknowledge my days at Jagori as those which sharpened my politics and understanding of issues related to women from a larger perspective. This will always remain with me.