Shodhini: the story of self-help and health in India

Shodhini: the story of self-help and health in India

In the 1980s, the women’s movement in Switzerland was losing steam. The change of name – from “Women's Liberation Movement” in the seventies to “Women's movement” – itself was significant; the word “liberation” was no longer present in it. With struggles for equal rights under the law, the tendency was towards institutionalization with offices for gender equality being set up in each canton. Bringing these struggles to fruition was to be a long adventure, but it evoked no passion in me though I was delighted that others were doing the work. Meanwhile, my feminist contacts were getting broadened when the International Women’s Health meetings in Geneva (1981), Amsterdam (1984) and Costa Rica (1987) brought together autonomous feminist groups.

After Central America, it was time for me to travel further to a continent I did not know yet, and whose political situation did not permit me to return. This was further east than my native country, Israel. Raised in a Jewish family, I hoped to return to Jerusalem one day but after the Six-Day war, I realized that Israel was no small country threatened by its neighbors. It was a powerful, colonial regime.

Then started my stint in India, a commitment for which I had planned to devote two years but stayed for five. I returned to Geneva at regular intervals for reasons of visa, among others, but this allowed me to participate in the famous women’s strike in 1991. It was the largest ever mobilization of women in Switzerland since the 1981 law for equality between women and men had still not been enacted. Our slogan was ‘Les femmes bras croisés, le pays perd pied’ or ‘women cross their arms, the country slips and falls’. It helped mobilize half a million women via unions and autonomous and institutional feminist groups. It was extraordinary.

In contrast, the feminist movements in India and Latin America were much more vibrant. Though I focused on women’s health issues, I also met with women’s groups and researchers working on other issues such as violence against women, working women’s issues as well as eco-feminism which began in India (Vandana Shiva and Maria Mies).

A Brief Summary of Women’s Health in India

Access to healthcare for poor women in rural areas is very difficult. Getting to a health center means losing a day’s work as well as paying for transportation; few women can do this and feed their families in the evening. Young boys receive more care that young girls. The mother is unquestionably the last one on the list of priorities. Similarly, girls’ food rations are smaller than those of boys. Boys have grown taller from generation-to-generation while girls have not. Finally, women often do not trust the Primary Health Centers. They think that behind the ostensible goal of providing maternal and child health services lurks coerced birth control, guided by a population control agenda. Women might hesitate to bring a child with diarrhea to a center for fear of forced sterilization! A third, sometimes even half of the medical personnel focus exclusively on promoting family planning. They frequently impose birth control, sometimes under duress, and much against the wishes of women.

The feminist movement is strongly opposed to abuses of modern western medicine, for example, the use of injected (NET-EN) or implanted (Norplant) progesterone contraceptives. Women cannot interrupt these even if complications arise; these also create undesirably long intervals between births. Modern ultra-sound techniques are often used unethically to determine the sex of the fetus and eliminate female fetuses.

Alongside these practices, western-oriented medical teams often have limited knowledge of traditional medicine. India has several traditional health systems, including Ayurvedic, Siddha and Unani medicines, each of which is popular. Middle-and upper-class women use allopathic medicine but happily send their domestic workers to healers from other health systems. The traditional healers are just as reluctant to share their knowledge as those in modern western medicine, and provide little effort to make it accessible to women.

In rural areas, a vast majority of the population is convinced that remedies of allopathic medicine (such as antibiotics) are the best even though they have no chance of accessing it, as indicated by the WHO. Since women mostly have to take care of themselves, it is truly in their interest to master simple and accessible methods based on plants and natural remedies.

The Beginning of the Project

My adventure in India started after I visited women’s health groups as well as feminist activists who wanted me to visit India.

The Shodhini project was a research-action study on medicinal plants and women’s health. It was launched in October 1987 when a national meeting on alternative medicine and women’s health was held in Tamil Nadu at the home of Fatima Burnad from Society for Rural Education and Development (SRED). There were about fifty women from urban and rural women’s groups with very different interests. The urban women wanted to learn from rural women what remained of folk knowledge about medicinal plants and women’s health. Rural women looked to urban women to learn about things to which they had no access, in particular, forms of contraception. Many workshops were organized: self-examination, fertility, pregnancy-related problems, sexuality, tumors, mental health, and contraception. Two projects emerged from that meeting: Shodhini and a pilot project on the use of diaphragms in India.

I accepted invitations from Indian groups interested in organizing self-help workshops for their teams, including SRED (Tamil Nadu), CHETNA (Centre for Health, Education, Training and Nutrition Awareness, Gujarat), and SUTRA (Social Uplift Through Rural Action, Himachal Pradesh). As in Central America, women from rural areas seize the opportunity to learn more about their bodies and sometimes organize to improve their health, when they have the chance to.

I also experienced difficulties. The workshop at the urban-wing of CHETNA brought together women who were leaders in the group’s hierarchy (the director and the administrative team), along with women from one of their rural groups (SEWA). At one point, one of the doctors declared “We are not ready to do self-help”, instead of saying “I am not ready to do self-help”. This had an extremely negative effect on others. In a follow-up discussion, she declared that violence against women does not happen in wealthy families. She placed herself above the others, and it was necessary to remove the stamp of class prejudice. In the end, five women came to the workshop; they represented neither the leadership nor peasant women, but middle-class women.

CHETNA took part in the project with DDS and Anveshi (Zahirabad and Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh), Action India, Jagori and Vikalp (New Delhi and Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh), Aikya (Chickmaglur, Karnataka), and Eclavya (Dewas, Madhya Pradesh). The core team included Philomena Vincent, Sarojini N, Renu Khanna, Anu Gupta, Bharti Roy, Smita Bajpai, Uma Maheswary, Indira Balachandran, our botanist and me. The collective benefited from the support and expertise of women who were doctors, particularly Shyama K. Narang and Veena Shatrugna.

Upon returning to Geneva, I threw myself into fundraising, and finally Mama Cash (Netherlands) and EZE (Germany) made it possible for us to begin the first phase of the project.

The self-help approach was presented by identifying the personal history of each woman and the neglected health problems for which they had little chance of finding help in their immediate communities. After workshops with women from different backgrounds (educated and illiterate, rural and urban), it turned out that gynecological problems were rampant. Menstrual problems (heavy, painful, or irregular periods), urinary or genital infections, tumors or cysts, as well as pregnancy-related issues were all too common. General health issues such as backache, painful joints, fatigue and depression were also prevalent and neglected. Those results corresponded to the research done by progressive doctors in three villages of Maharashtra. The study, published in The Lancet, revealed that 90 per cent of women suffered from gynecological problems, but only 10 per cent sought help.

The First Phase

Groups were formed in five rural and one poor urban region. Each consisted of a dozen participants that included practically-trained midwives and local leaders. The training brought them together regularly and was based on the self-help approach. Starting from their own health problems, participants discovered their own anatomies and genitals. With a speculum, a mirror and a flashlight, they got to know their cervix and learnt to perform a two-handed examination. Mastering that step signifies taking back the control over their bodies and lives! We also shared life stories to better understand myths and beliefs about health, illness and healing processes. That method permitted us to not only document all of the above but also better understand how we all functioned.

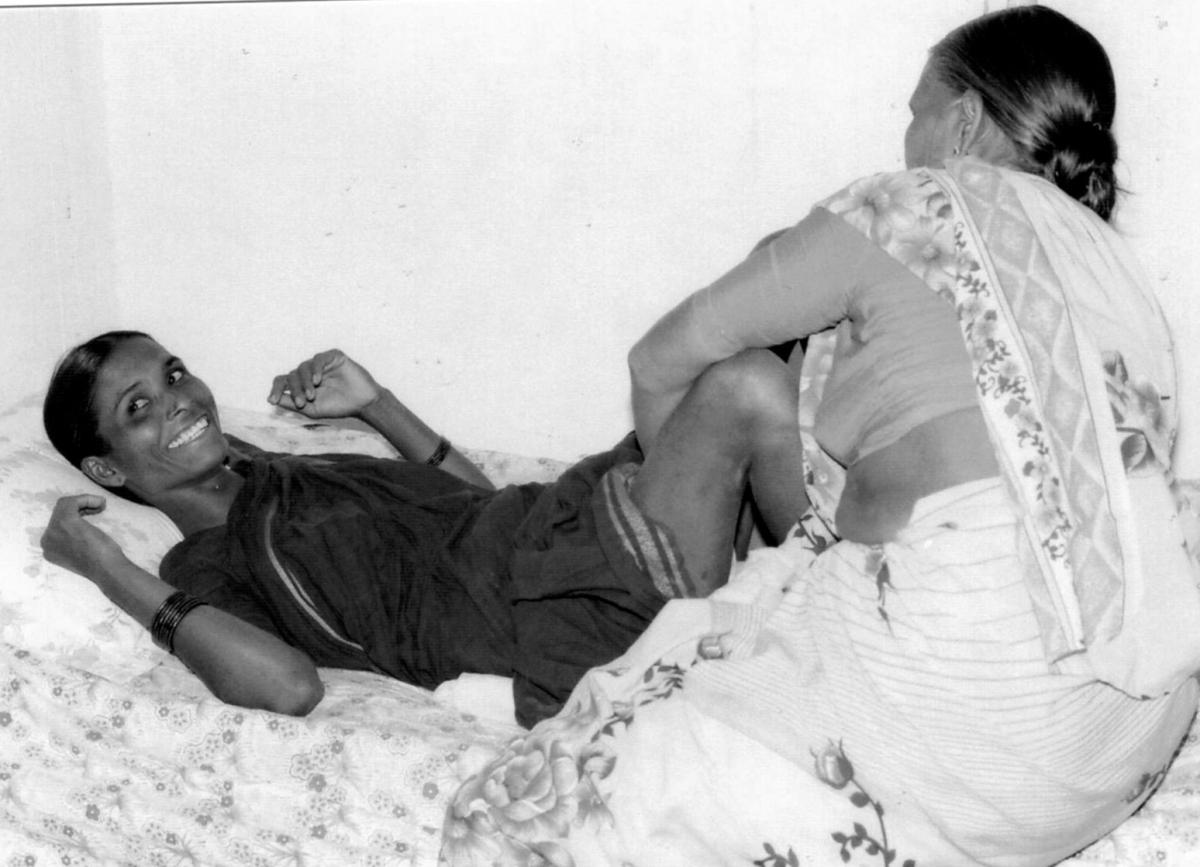

Apprenticeship of two-handed vaginal examination at the Deccan Development Society, Zahirabad, Andhra Pradesh (1992)

At the same time, women sought out healers in their region to find recipes for simple remedies (with a maximum three ingredients) to treat the most common of women’s illnesses. This way they preserved what remained of that oral and written knowledge. Since most of the women were illiterate, it was necessary to find appropriate means of communication and documentation (for example, illustrated prescriptions and role playing). In collecting information on medicinal plants, the help of literate women was essential. Due to the large number of common names for any given plant, a herbarium had to be constituted. Definitive identifications fell to our botanist from the Kottakkal Herbal Garden in Kerala.

The results were quite impressive. After eighteen months, we had collected 600 entries corresponding to about 300 plants, with their properties and the symptoms for which they could be used. By verifying our findings against the available literature, it was found that the largest part (classed as ‘A’) corresponded to specialized publications for the same properties and uses. The second part of the findings (classed as ‘B’) comprised plants mentioned in specialized publications but for which the specific indications for women’s health were not known. Only fourteen findings were classified as dangerous or toxic (classed as ‘C’) and removed, for example a remedy for insomnia extracted from the excrement of female swallows. These results provided credibility to the orally-transmitted knowledge gathered by women, and opened up new fields of research.

And the Second Phase…

During this time, Renu Khanna and her group (SAHAJ or Society for Health Alternatives) from Baroda joined the collective. The women’s trainings continued and became more refined. To validate the efficacy of a plant, a thorough questioning that included antecedents, a detailed description of the symptoms and a complete examination were necessary. The health workers had to be able to make a precise diagnosis, independently of the patient’s complaints and through their own observations and examinations. During the workshops, simple preparations were made, including infusions, decoctions, powders and pastes. The most sophisticated preparations were the herbal tinctures (macerations in alcohol).

The second phase consisted of clinically testing the collected information. We started with workers who were beginning to feel at ease with plant-based preparations. They became more autonomous in their villages and obtained recognition, thanks to the effectiveness of plants with known properties.

The first series of plants tested comprised 35 from class ‘A’ and were used for problems such as vaginal discharge, stinging during urination, anemia, and problems linked to nutrition, as well as painful menstrual periods. A year later, after having shared the feedback of our experiments, we began a second series of clinical tests on 36 other plants from classes A and B, for menstrual irregularities, uterine prolapse, overly heavy periods, and complications during pregnancy and childbirth.

This progressive approach proved very effective. Health workers were able to distinguish whether vaginal discharge was due to anemia, infection, pH imbalance or if it was perfectly normal. They could differentiate between heavy periods with or without fibromas, were comfortable providing nutritional counseling, and had advanced into more complex areas such as extra-menstrual bleeding that may be linked to hormonal imbalance (estrogen or progesterone). Women workers could also tackle fertility problems, without losing sight of the emotional aspects and the living and working conditions of those they counseled. They became formidable “barefoot gynecologists” and gained confidence thanks to improvements in their own health and that of the women in their villages.

Sudha’s Story

Sudha, a member of a local group from DDS (Zahirabad, Andhra Pradesh), offers an excellent case study.

A widow with two sons, Sudha was like many other widows in India whose social position and self-esteem were very low. She was tall and under-weight. She suffered from heavy periods, fatigue, backaches, poor night vision, and was very likely anemic. She had seen the local nurse from her region who proposed a treatment of iron pills, but she stopped the treatment as it caused her constipation.

Sudha had a patch of land right in front of her home, but her brother-in-law who owned the adjacent property systematically irrigated his land without leaving enough water for hers. Those of us from the local group suggested she plant leafy green vegetables on her land. We visited her regularly ostensibly to have tea, but also to insure that she dared to irrigate her land. With those leafy greens, she could nutritionally complement her dal (lentil). That was a way of raising her iron levels that fit better with her lifestyle. And little-by-little the symptoms diminished, since anemia causes bleeding. By adding a plant-based hormonal regulator to inhibit the growth of extra-endometrial tissue, and thereby the bleeding, her fatigue was reduced.

Sudha’s self-confidence was renewed and her nutritional intake improved. As a result, she was more convincing when sharing her experiences with other women and explaining the importance and the possibilities for treating anemia.

My Role

During that period, my role as project coordinator was to regularly visit each group for self-help workshops, training and discussions about the method (its joys and difficulties).

That involved a lot of travel. In the south I was based in Bangalore, and in north in New Delhi. To get from Bangalore to Zahirabad (Andhra Pradesh), for instance, I had to take the night train, then a bus, and finally a bullock cart. It was a bit tiring, but the support network was extraordinary. I was welcomed and housed at the homes of friends (both women and men) wherever I went and also met other incredible people. In each group I learned the rudiments of the local language. I know how to say ‘vaginal discharge’ in several languages—this is good for a lot of laughs!

Among the coordinators, we used English. It was the language that connected us, as none of the languages spoken in the different groups (Hindi, Gujarati, Telugu, Tamil, Kannada) were spoken everywhere from north to south.

Every six months, the coordinators’ collective met to improve our organization. That group also had its self-help workshop which took some time but strengthened the group. At the fourth group meeting, Philomena Vincent from Aikya said, “What I like in the self-help approach is that everyone has to participate fully as a person, which is not the case in other programs.”

The highlights of this experience were also the organized meetings among local groups from the original Shodhini collective. For example, women from DDS (Zahirabad, Andhra Pradesh) met those from Vikalp (Uttar Pradesh). Renu Khanna (Sahaj, Baroda) organized a meeting (mela) that brought together a hundred odd public health workers. They didn’t necessarily speak the same language, but the coordinators and a few bilinguals translated.

At the end of each phase, I returned to Switzerland and resumed fundraising to continue the program. The funding went directly to the local groups. One group had to withdraw because its coordinator wanted to withhold 25 per cent of the funding for herself! After EZE, we were able to interest NORAD (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation) and DANIDA (Danish International Development Agency). Then on, I no longer did any fundraising; Philomena and later Renu took over the job.

Dissemination Phase

Upon returning from the Philippines, we began the phase of dissemination and publication. Local groups had acquired enough confidence, skills and dexterity to be able to share their knowledge and practice with other women and groups. New people/groups joined the network without attending my training or meeting me. The time had come for me to return to Switzerland.

The principal work of the Shodhini collective was to prepare a publication, first in English. We shared various aspects amongst ourselves and revised them together. One would work more on history and methodology, another on beliefs… It was to be a real collective undertaking with ten authors for one publication. Touch Me, Touch Me Not: Women, Healing and Plants was published in 1997 by Kali Women’s Press in New Delhi (now Zubaan). An edition in Hindi was also published, and articles appeared in the local press (N. B. Sarojini, “The Barefoot Gynecologist” in Human Landscape).

Cover of the English edition of Touch Me, Touch Me Not

The difference between the self-help approach and that of family planning is found at the decision-making level: in self-help groups, women themselves determine their priorities in tandem with their health needs. In family planning centers, the priorities are imposed. When women in India are asked about their priorities, they focus on essentials: food, potable water and decent housing. Health concerns follow later: weakness (anemia), bleeding, infections, fibromas, prolapsed cervix, pregnancy-and childbirth-related problems, as well as general problems such as backache, painful joints or depression. Fertility is of much greater concern to them than contraception. Due to the lack of retirement insurance and a high infant mortality rate, pregnancies and living children are essential for survival.

Our philosophy is that women must be able to solve their problems based on their own priorities. They will only take care of their own health when other primordial concerns, such as housing or food have been addressed. But they also need to be encouraged, like women in the west, to not always put the needs of others before their own!

The Shodhini adventure was my most fully-developed self-help experience.

This photo from 1992 shows a group of us in Godhra (Gujarat) in front of the bus belonging to SARTHI (Social Action for Rural and Tribal inhabitants of India). The plant I am looking at is an Calotropis procera, an abortifacient whose branch is used for physical induction; it is also anti-malarial.

References:

Nissim, Rina (2003), ‘Plantes médicinales et santé des femmes en Inde, une recherche-action sur une efficacité et toxicité surprenante(s)’ or Medicinal Plants and Women’s Health in India: research-action on efficiency and toxicity’, a thesis submitted for validation of training at the Institute of Applied Ethnopharmacology, Metz.

Nissim, Rina (2012), ‘Genre, changements agraires et alimentation’ or ‘Gender, Agrarian Changes and Nutrition’ in Christine Verschuur and L’Harmattan Eds., Cahiers genre et développement, N. 8 (Graduate Institute of Geneva).

This article is based on a chapter in Rina Nissim’s 1952 book Une sorcière des temps modernes, le self-help et le mouvement femmes et santé (A witch of modern times: self-help and the women and health movement).